- Home

- Michael Guillebeau

MAD Librarian Page 2

MAD Librarian Read online

Page 2

“Janice?” she said. “Tell me you’ve got some good karma for me there.”

There was a long, awkward pause. “I hope this is about lunch, Serenity. I’d love to do lunch with you. But if this is about the library’s bill, I can’t do anything about that. Today is turn off day for the library. Four o’clock, and you know it.”

Serenity studied the rat, and the broken shelf on the wall behind him. “Janice, we’re the library, for Christ’s sake. We can make do without a lot, but we can’t function without internet. The day we lose our internet is the day we close our doors.”

“And internet providers can’t function without money. Serenity, don’t do this to me. Look, why don’t you put out a collection jar, ask for donations?”

“If you’ll accept whatever I collect today as partial payment, I’ll bring the money to you personally.”

Janice paused. “No, sorry. I just looked at the account. You owe a lot more than any collection or donor can come up with. And my boss is insisting on full payment this time.” She sighed. “Serenity, you know I support the library, but I’ve got a boss, just like you do. I’ve got to give him something. Now.”

“C’mon, Janice. You know that’s not fair, we’re the library. I know for a fact that you let TLA Aerospace slide a lot longer.”

“Yeah. And while TLA didn’t have enough money to pay their bills, they still found money to contribute to every local politician—and get a tax credit for it to boot. And their president plays golf with my boss. They got connections. You don’t.”

Serenity looked at a set of dog-eared blueprints pinned to the wall, starting to yellow. “Yeah. Been told.”

There was silence, then Janice said, “Have you tried short skirts and push-up bras?”

“Only on Joe. How long have we got, really?”

Long silence. “Don’t do this to me. Four o’clock. My boss will be knocking on my door at four-fifteen for confirmation that I’ve cut you off.”

Serenity took a deep breath. “But he would rather have money. What if I could promise you that the bill will be paid in full by Friday?”

There was a long pause. “I’d laugh at anybody else who said that, Serenity. But you and Joe are the only people left in town famous for being absolutely honest. If I guarantee my boss that payment is coming, then my ass is on the line. And yours. If you don’t come through, I’ll be in trouble and nobody will let the library slide on anything ever again––and the library always needs to slide on almost everything. You are absolutely, positively sure you can do this?”

Serenity looked at the screen and saw the string of zeroes that represented her projected income. Then she looked at the rat, who was exploring his rum. He looked up at her and she took his head bob as encouragement. Maybe karma really could work by Friday. She downed the rest of the rum.

“I absolutely, positively promise.”

She didn’t feel illuminated.

three

little women

TWO SKINNY WOMEN DRIFTED into Serenity’s office, just as they did every day at eleven o’clock.

Doom—nobody called her Amanda with a last name like that—was a model-thin young black woman with coffee-and-cream skin, and a taste for tight superhero t-shirts and tighter jeans. Joy Quexnt—nobody called her Quexnt with a last name like that—was as old as Doom was young, and skinny even compared to Doom. She peeled off a white oxford shirt. The Grateful Dead tank top underneath showed her skeletal white arms covered with blue tattoos.

“Remember,” Serenity said. “Keep the shirt on out on the floor. Our city council doesn’t like tattoos.”

Joy gave her a terse nod. Doom tried to sit on the edge of a crooked wooden chair that was in the corner by the door. The chair cracked and settled half way down and Doom jumped and balanced half on the chair and half in the air. Joy ignored this and slumped into the one functional visitor’s chair and studied a fresh patch of blue ink on one of her skinny arms.

“This place is a dump,” she said. “Broke chairs, broke toilets, a headless tin man in the playground from where kids were throwing rocks at him. And slow Wi-Fi.” Her tattoo seemed to pass some test and she dropped her arm into her lap, right next to her other white-skinned blue-tattooed snake of an arm.

Serenity watched Doom’s chair to see if it was done adjusting itself. Satisfied that it was as stable as anything else in the room, she sat relaxed in her chair and sipped her Myers’s. “What it is, is the best we can do with what we’ve got. This city needs us and our books, whether it knows it or not. Until the city figures that out, we’ve got to keep the public areas working as best we can. That includes rotating the broken-down furniture from the public spaces into the offices and being careful how we sit.”

The rat scampered out from his home in the books, took a long leap onto Serenity’s desk, climbed up on her coffee cup, and took a long whiz there. All three of the humans stared at the desk, as horrified as the rat was unconcerned.

The big, brown-and-gray-and-dirt colored Alabama Roof Rat (Rattus Alexandrinus Geoffroy—you could find his picture in 598.097, Peterson Field Guide to Mammals of North America, on Shelf 37) stared back at them and seemed to grin.

Doom snatched a book from the nearest stack and hurled herself straight up in the air, the book poised over her head like a sword of vengeance from the graphic novels she lived for. She screamed at the top of her arc then crashed down to smash the rat and the cup. Brown liquid, rat pee, and pottery shards exploded like a small mushroom cloud and settled all over the messy stacks of papers, cards, books, CDs, pink message forms, invoices, yellow post-its and leftover food on Serenity’s desk. In the end, the rat lay motionless on his back with his feet sticking up in the air.

“Jesus Christ, Doom.” Serenity dug a handful of paper napkins from yesterday’s half-eaten Wendy’s lunch and wiped down a now-stained book. Then she held it up and shook it at Doom. “Look at this. That’s a review copy from a local author. What am I supposed to tell Mike?”

Joy glanced up sideways from studying her fingernails and said, “Tell him the rat gave him his first honest review.”

Serenity glared and sopped up liquid.

“Ms. Hammer, he was peeing in your coffee,” said Doom. “He’s a rat.”

“He was our rat. We protect things around here.” In the middle of the mess, she poked the dead rat. The rat flipped over, hissed at her, and ran back into the clutter.

“Thank God Faulkner’s all right,” Serenity said.

Doom said, “He’s got a name?”

“He’s good luck, and we need all the luck we can get.”

Doom wasn’t convinced. Serenity looked at her. “I let you keep your good-luck spike. I’ve got my rat.”

“My spike is an actual library spike, a sharp hand-made nail from Colonial times set in a wooden base. It’s from America’s original library in Philadelphia, probably used by Ben Franklin himself to keep track of important papers by spiking them. That’s where the phrase, ‘spiking a story’ came from with newspapers—”

“Yeah, I know, I’ve heard it,” Serenity said. “I know spikes like yours used to be important in libraries and newspapers. But now they’re just a hazard to children—and others. I told you, you could keep it, as long as it stays high on the shelf behind your desk, where it can’t hurt anybody.”

“It does. I use it to keep notes on great chapters from my murder book club. I read about a great way to kill somebody and bam! It goes on the spike.”

“Jesus,” Serenity rolled her eyes. “This is supposed to be a library, not murder for hire.”

“What it is, is a dump,” said Joy.

“You said that already.” Serenity stuffed the wet napkins in the trash and sat down. “Let’s get back to budgets.” She pulled up a coffee-and-rat-pee-stained sheet and squinted at it.

“Rat should have peed on the budgets,” said Joy.

Serenity shook liquid off the paper. “Thanks to Doom, he did. Like everybody else.”

“How bad?” said Doom.

“Bad. The council is divided between our backers, who think that, since we’re already one of the best small libraries in the South—” Joy snorted and Serenity glared at her “—we don’t need more money.”

“And then there is the Evil One,” said Doom.

“Councilman Bentley’s not evil,” said Serenity. “He just wants to zero out the library budget and give everyone in the city Amazon discounts.”

“Evil.”

Serenity stared at the numbers floating on the brown-stained paper. “Maybe. He couldn’t convince the council to de-fund us completely, but he got them to slash our budget to the bone for next year. And they’ve given us nothing for right now. Even if I can find a way to pay our bills over the next few days, I don’t see a way out long term. Either we cut back on buying books or cut salaries. Or close. And that’s a real possibility if we don’t do something.”

Doom jumped up and clenched her fist in the air. “We don’t cut books. Books are our power.”

Serenity said, “Well, look around you. We’re the only three full-time paid employees left. We’re each doing two jobs, and the volunteers and part-time kids out there are doing more than their share. We are barely keeping up with getting books to people as it is. And it’s getting worse. Because we’re so short-handed, we get more complaints. If we can’t do something soon, we won’t have time to do anything but handle complaints.”

Doom stabbed a set of dog-eared blueprints that covered one wall. “That’s why we’ve got to push hard for a better future. What does their precious budget say about the library expansion we all know this city needs?”

Serenity closed her eyes. “Not happening this year. Same words that we heard last year. While the last mayor found t

he money two years ago to clear the land next door and pour the slab for the expansion, current conditions—that’s their phrase—do not permit us to complete the project at this time.”

Doom slapped the blueprints. “No tutoring area for kids and teachers?”

“No.”

Doom slapped them harder. “No incubator for writers and entrepreneurs, small creators who can use the library to form the creative core of the city?”

“No.”

Joy mumbled. “Not even the coffee shop?”

Serenity opened her eyes but couldn’t look at either Joy or Doom. “Maybe next year. You know how it goes. Every year, I go back and beg the council. Sometimes I get some money; sometimes not. It’s the way the game’s played.”

Doom uttered an un-library-like expletive and dropped herself back into her chair. “Screw the game. We’re not giving up books. Cut my salary.”

“Not mine,” said Joy. “Got a spot on my stomach just itching for skin art of the Last Supper with the masters of rock and roll as disciples.”

“I’m not cutting anybody’s salary. You two are all we’ve got. It’s my job to get my ass out there and beg for a little more. Enough to keep us alive.”

Doom had her arms folded. “I will not give up. You said we were going to build something new, starting right here in Maddington. A place where, when people had questions, they got answers. When people needed help, they got help. A city of books; a city built on knowledge and its power. You said that. Was that just talk?”

Serenity looked at the ceiling. “Yes, it was.”

four

jiminy damn cricket

THE WOMEN LEFT. Serenity reached over to the table and picked up a blue mug with the words she blinded me with library science on it. Then she took out the Myers’s for reinforcement. Halfway through pouring, she looked up and saw Joy slouching at the door, pulling her long-sleeved shirt on.

“That’s not coffee,” Joy said.

Serenity took a long sip and the smooth, sweet burn took her away to a Florida Panhandle beach with white sands and gentle waves.

“Ain’t rat pee either,” she said.

“Good point.”

Joy was studying her arm. “You need something, Joy?”

“No. But you do.” Joy looked up from her arm. “Here’s the thing. If you keep eating shit, all they’ll do is let you—and the library and the city—eat more shit. That’s the game they’ve got you playing.”

“Who’s they?”

“The rulers of the world, particularly here in sweet little Maddington. The big dogs and the big crooks and the big corporations that run this city like their own personal trough.”

“Joy.”

“Really, did you not see The Matrix? Whole movie was based on the idea that everything we think we see is just an illusion created by the evil real world to keep us asleep and happy, while the masters rip off the world and take what they want and leave us with crumbs. Everybody liked that movie because, deep down, they knew it was the model for their own little city.”

“I think some of your tattoo ink went to your brain.”

“Can’t you hear the masters laughing behind your back while you’re begging for scraps?” Joy asked. “Then they take all the good stuff for themselves and dare the world to stop them. Don’t you know how to read those polite rejection letters they send you?”

“Of course I know how to read,” said Serenity.

“No, you know how to read nice things, like an RSVP to a tea party. The real world ain’t no tea party—particularly here in Maddington. You need something to translate nice-speak to real-speak before you read anything else from the masters of the dirty world. Here. Pick up any of the polite letters you’ve got explaining why rich and powerful people can’t contribute to the library.”

Serenity rummaged through a stack and came up with a letter written on expensive paper. “Here’s a letter from Lois Treland. She’s a very nice lady who wanted to help but couldn’t.”

“Treland?” Joy asked. “The developer who was almost bankrupt until our local congressman told the EPA that the land she wanted to build on wasn’t really wetlands, it was just a temporary vacation spot for ducks who could be happily relocated by hunters?”

“Yeah.”

“So now Treland’s rich. Richer. Okay. I haven’t seen the letter, right?”

Serenity nodded.

“Let’s read it out loud,” Joy said. “Except that, anywhere they say, ‘we care deeply,’ read, ‘we don’t give a shit.’ Anywhere you see, ‘we see the value of your project,’ read, ‘we don’t see how this could possibly give us more hookers or high-quality cocaine.’ And any sentence with the word ‘nice’ in it becomes ‘go to hell.’ Now read.”

Serenity looked down at the paper.

“Out loud, please,” said Joy. “I think you need the education.”

Serenity grumped but read.

“Dear Ms. Hammer.” She raised an eyebrow to Joy to show how polite this was.

“I . . .” Serenity hesitated, but made the change. “. . . don’t give a shit about the needs of the city of Maddington. While the Maddington Library is a shining jewel of our community, I . . . do not see how it can supply us with more hookers or high-quality cocaine. Therefore, I must regretfully decline, but be assured that I sincerely wish that you and the library have a nice day.” Serenity paused and looked evenly at Joy as she corrected the last sentence.

“I sincerely wish that you and the library would go to hell.”

Now Joy raised an eyebrow. “Does that feel about right?”

“Yes. No. I don’t know. Somedays. In any case, thanks for your input. It’s good for us to have an ex-cop in here. Little different attitude than most librarians.”

Joy laughed. “Yeah, I’m the MAD Jiminy Damn Cricket. And you don’t want to know the translation for ‘thanks for your input.’”

“No, I mean it, Ms. Cricket,” said Serenity. “Thanks. But what difference does it make? They’ve still got everything we need.”

“That’s because they’ve got everything they can steal, and lawyers and political action committees to see that they don’t go to jail. And, they know that nice people like you will be satisfied begging for rat pee.”

“Begging is all I’ve got.”

Just then the phone rang, and Serenity punched the speaker button.

“Maddington Library. Serenity Hammer speaking.”

“Lie-brarian Hammer, I want you in my office in ten minutes.”

“Councilman Bentley.”

“Councilman Doctor Bentley. My office manager said you wanted to waste some of my time. I’ve got time in ten minutes. After that, I’m booked all week.”

“I’ll be there.”

“Hurry up.”

“Yes, sir.” She took a sip of rum and looked over at Joy. “And Councilman?”

“What?”

Serenity purred. “Have a very nice day.”

five

rectal thermometer

COUNCILMAN DOCTOR BENTLEY was a pediatrician popular with every parent in Maddington who wanted someone to be tough on their kids. That left him plenty of time to be a city councilman who was tough on the city and the money-wasting bureaucrats who worked for it.

Serenity had been sitting alone in Doctor Bentley’s waiting room for thirty minutes, reading three-year-old Highlights magazines and an ageless Bible Stories in Pictures. She looked at the receptionist behind her Plexiglas window and smiled. Sharon smiled back, so Serenity stood up and walked over, if only for the change.

Sharon slid the window open.

“Sharon, Doctor Bentley said he was in a hurry for me to get here. Can you check to see what he’s doing?”

A shake of the head. “Be careful. He gets mad if you just call him ‘Doctor’ anymore. It’s ‘Councilman Doctor Bentley.’ And he’s doing the same thing he’s always doing. Reading political magazines and fishing magazines. We’ve only had two appointments this entire afternoon. I’m bored out of my head, like most days.”

“Then why––”

“He likes to make everyone wait at least twenty minutes, so they know he’s important.” She looked at the clock and smiled hopefully at Serenity. “Shouldn’t be much longer.”

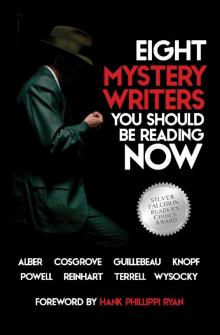

Eight Mystery Writers You Should Be Reaing Nowwww

Eight Mystery Writers You Should Be Reaing Nowwww